| |

LEAFS — CR 1471 Site |

This LEAFS site is located on the right hand side of CR 1471, about a half-mile from the intersection where that road leaves U.S. 301. As you drive up, the parking area is to the left of the welcome sign. ( A small parking area is next to the entrance to the interpretive trail where visitors may leave a few cars.

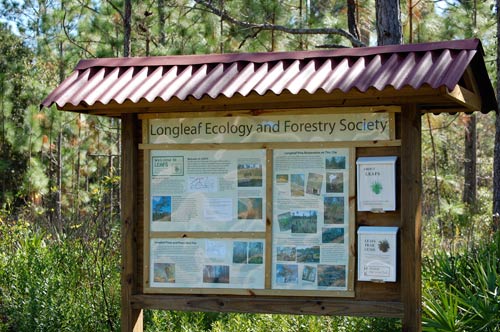

An informational kiosk is located in the parking area. There we can pick up a guide telling about the numbered stops along the trail. As we walk along, we’ll pause at each of the stops and read the entry in the guide. Perhaps you’ll have some questions. If so, we’d be glad for you to contact us.

The Trail Guide begins with an introduction which tell us: On the short walk you are about to take you will pass the numbered markers described below. As you stop at these you may read about the restoration of this site as an example of a longleaf pine ecosystem. This is not a nature preserve where all plants are protected, but a working forest where from time to time some trees are harvested to produce timber. Despite that, this trail may resemble a nature trail such as one you might find in a state park, as the LEAFS project strives to retain as many natural features and native plants and wildlife as possible. Many years ago a native longleaf forest grew on this site's 90 acres. Restoration started here in 1993 and is on-going. The project’s objective is to demonstrate to small private landowners how a longleaf pine ecosystem, managed primarily with prescribed fire, can economically produce a sustainable harvest of timber without markedly upsetting the balance of nature.

We’re still within sight of the parking area when we come to the first stop on the trail. As you can see from this picture, the section to the right of the trail has recently been burned. We’ll read the entry in the Trail Guide: 1. Over 100 years ago, the entire LEAFS tract—as well as most of the surrounding property—was covered with a virgin forest of huge longleaf pine trees. Those trees—many of them hundreds of years old—could well have stood over 80 feet tall and been so broad that you could not wrap your arms around the trunks. Now they are all gone, harvested years ago by the early settlers of this section of Florida. The trees that grew back in their place have also been harvested. Although the site has been logged several times, much of the native understory and ground cover has persisted. Before restoration was started, there had been no fire on the site for over 20 years, resulting in many encroaching slash pines and broadleaved trees, primarily water oaks, such as those nearby ahead on the left.

Prescribed fires have now killed most of the water oaks. But as we walk along, we pass a water oak left to show what some of the invading trees looked like before fire was reintroduced to this site.

After we pass that water oak, we come into an area where there is very little thick understory, but many young pines. We’re approaching our second stop where we can read an explanation in the Trail Guide: 2. What you see here is a mixture of young longleaf and slash pines. Former owners, preparing to build a commercial greenhouse here, scraped all the topsoil and vegetation from this site in the 1980’s. Now there is little understory. For instance, you’ll note the absence of thick saw palmetto, such as that you walked past a moment ago. The greenhouse was never completed and the site stood empty, with bare mineral soil exposed. This condition resembled that which would occur after a very hot fire, and pine seedlings quickly established themselves. Had there been any fire when the seedlings were smaller, it’s likely that most of the slash pines would have been killed, leaving only longleafs, a pine species which is both fire-resistant and fire-dependent.

Leaving these young trees, we pass through a cut made in a mound of the topsoil bulldozed to clear for the greenhouse and see up ahead the post with the number three on it: 3. To clear the LEAFS tract of encroaching broadleaved trees, which are vulnerable to fire, the entire tract was burned on a cool winter night in 1993. Due to the many years of fire exclusion, the competing vegetation was then quite thick, preventing pines from regenerating well. Beyond the few larger trees you see in front of you, there were almost no young pines in the area behind this marker. After another prescribed fire for site preparation in 1994, thousands of container-grown longleaf seedlings were planted, followed by more prescribed fires every few years and more plantings. Some of the young pines you’ll pass ahead where the trail bears to the right are from those initial plantings.

Even though they are carefully planned and monitored, prescribed fires can produce dramatic flames. As the LEAFS site is closed for safety during prescribed fires, we won’t encounter any scenes such as this during our walk.

But it’s likely we’ll pass some sections which have been recently burned. Here we’re on the other side of that section which we passed at Stop 1.

After a section has been burned, it can be planted with seedlings such as this. As we’ll see later on, there are places where mature trees produce enough seed that supplemental planting usually is not necessary.

We come to a fork in the trail at this birdbox. This is a loop trail. The fork on the left is where it loops back. We’ll head off to the right. Before we go, look closely at that birdbox on the tree. What’s in it?

Probably flying squirrels. The birdboxes were intended for bluebirds -- and sometimes are even used by them! -- but more often they are taken over by the little nocturnal relatives of the larger cousins so often found in suburban backyards. That’s all right, for they need homes, too. It turns out that the boxes mounted on trees are the ones flying squirrels mostly use. Boxes mounted on posts are more likely to have bluebirds.

We pass through a section where there are young pines planted about 10 years ago and doing well. As we walk along past these trees, we come to pines which are much larger and after a bit we reach Stop 4.

Here the Trail Guide tells us: 4. These larger pines are the best example on the LEAFS tract of what an older longleaf forest might look like. The trees are widely spaced and the understory is not impenetrably thick. Most of the larger trees you see are longleaf pines, but there are a few loblolly and slash pines. At this age and size, these trees will easily withstand the fires of prescribed burns. Note the blackened trunks. When the trees in this area are harvested, some of the longleaf pines will not be cut. They will serve as a seed source. In this shelterwood method of regeneration, prescribed fires will keep the ground in this area free of thick vegetation so that the longleaf seeds will fall on bare mineral soil. Once seedlings have become well-established, the remaining older trees may be removed. The shelterwood method, as opposed to clearcutting, avoids the considerable expenses of replanting.

Continuing on the path through these taller trees, we might think that a longleaf pine forest which is regularly burned is pretty monotonous—pine tree after pine tree after pine tree. That is pretty much the case, as few other trees are able to survive frequent fires. Before fire was reintroduced to this site, as mentioned previously, there were many water oaks, as well as some other broadleaved trees. Just before we reach Stop 5, we pass a dahoon holly. As with all hollies, it produces attractive red berries (which are still green in this picture). Across a fireline and only a few feet away is the marker for Stop 5. There we’ll read: 5. This is the main fireline bisecting the LEAFS tract. You have already passed other firelines which divide the tract into many small blocks for use in the periodic prescribed burns which are conducted here. Longleaf pines are a fire-adapted species, not only withstanding frequent fires, but actually requiring them to successfully regenerate themselves. Young longleaf seedlings look much like tufts of grass. They often remain in this “grass stage” for a number of years while their long taproots continue to grow; then they will shoot up rapidly.

On an actual walk here we would have already passed many longleaf seedlings on the edge of the trail. As you can see from this picture, the one on the right has put out a “candle” and is about to start making rapid height growth. Now we’re leaving behind the larger trees and are walking through some more open areas. There are a few scattered larger trees. Some of them are longleafs and now that fire has been reintroduced to this site, their seeds are finding spots where they can germinate. So some of the young longleaf seedlings you’ll see are from these parent trees. Other seedling have been planted by LEAFS.

At our next stop, the Trail Guide is going to ask us to look for some snags. Actually, the ones the Trail Guide refers to have long since fallen, but if we look around, we’re likely to find some others. The extremely dry weather sometimes experienced in Florida can be very stressful on trees. Longleafs may withstand these stresses better than some other pine species, but they are not totally immune, and sometime prescribed fires kill a weakened tree or two. Trees hit by summer lightning also often die. Here’s our next stop: 6. As you walk along this trail, you may see a few large dead trees, known as snags. Some pine trees, including longleafs, are invariably killed by fires. Sometimes it’s because the conditions for a fire were not correct and the fire burned too hot—the weather was too dry or perhaps the wind picked up after the fire was set. But more often a tree dies in a fire because it was already sick and weakened; perhaps it had been struck by lightning. Even without a fire, the stress of a few hot and dry summers in a row might kill such a weakened tree. If a lot of trees are killed, as might happen if a fire burns too hot, it could be economical to salvage them within a few weeks of the fire. But when only a few die, they are often left standing. Snags are important homes and food sources for wildlife, notably flying squirrels and a variety of birds, including woodpeckers and other cavity-nesting bird species, such as chickadee, bluebird, and titmouse. Where we’re looking for snags, we’re not far from the highway (CR 1471) and some of the homes bordering the south side of this site, but we’re about to turn and walk into the interior.

After a bit we’ll come to Stop 7 where a small water oak has sprouted next to the marker and we read in the Trail Guide: 7. Except for a few scattered larger pines in front of you there was little natural regeneration in this area. Because of the long exclusion of fire, there were many large water oaks here. Some survived the initial site preparation burn and it was necessary to either girdle them or cut them down. Even then the stumps often resprouted, and while a second site preparation burn eliminated some of the sprouts, it was necessary to apply a spot herbicide to the remainder before longleaf seedlings would grow well here. Like most pines, longleafs are intolerant of thick shade and require bright sun for full growth.

As the Trail Guide discusses, it was necessary to apply herbicide in this area to control the problem water oaks. Springtime prescribed fire, applied just as water oaks are putting out new growth, is often very effective. Cooler winter fires are not as lethal. They will kill oak sprouts down to the ground, but extensive roots quickly send up new shoots. These shoots can grow rapidly and shade out young pine seedlings.

Now we’ll walk on and cross another fireline as we come to our next stop: 8. As the trail winds around under these mixed pines, you might try to distinguish the three common species found on the LEAFS tract: longleaf, slash, and loblolly. Many years ago, it’s likely that the pines here were almost exclusively longleafs. In the absence of fire, litter built up on the forest floor, which also became increasingly shady as the understory grew. Longleaf seeds are larger than those of the other species and must fall on almost bare mineral soil to germinate. In the thick litter on the forest floor, longleafs failed to reproduce. But slash pines did, and since there was no fire to check them, they are quite numerous. As we walk past these young trees mentioned in the Trail Guide, you might notice that they are rather closely spaced. But they are not as closely spaced as they once were, as several prescribed fires have thinned them quite a bit. At this age and size, slash and loblolly pines are resistant to fires, but they are not “fire-proof.” You can see that some of the pines in this picture have been killed. As we walk on, soon we pass yet another fireline. As we’re making a loop, we crossed this same fireline only about 200 feet from here.

At our next stop, the Trail Guide discusses some of the understory plants. One of the most attractive is tarflower. Here’s the Trail Guide entry: 9. In the millions of years in which longleaf pines evolved in the presence of natural fires—primarily caused by summer lightning—other plants were also becoming adapted to fire and dependent on it for their survival. The understory and ground cover in a longleaf ecosystem have many such plants. Fire kills them to the ground, but the roots soon send up new growth. Saw palmetto is the best example, but there are many others. In early summer, you may see an abundance of tarflower blooms, delicate seven-petaled flowers that are somewhat sticky. Another summer flower is hairy laurel, a relative of mountain laurel. These low-growing shrubs with attractive pink flowers may be found on sections of this trail. Also common on the LEAFS tract are meadow beauty, several types of blueberries, and grass pink, an orchid. All of these plants contribute to a rich diversity which is often lacking in pine plantations where extensive site preparation has been conducted.

The sections where this group is gathered now has been burned several times, most recently in 2009. After each fire, everything was blackened, but now there is fresh new green growth. There is plenty of saw palmetto and gallberry, but it isn’t quite as thick as before being burned.

In the summer and fall, especially after a spring or summer fire, where we’re walking now is likely to be covered with the purple flowers of deer tongue. Soon we’re at Stop 10 where the Trail Guide tells us: 10. This section of the trail passes through more mixed longleaf and slash pines. When restoration of the LEAFS tract began, there were many young slash pines among the sapling-sized trees. In the years since then, periodic fires have killed most of the slash pine seedlings. On the other hand, most longleaf seedlings have survived, and as the larger longleafs here mature and start to produce seed-bearing cones, longleafs will increasingly predominate in the mixture of trees. It will probably not be necessary to undertake any further supplemental planting in this area. We’ll walk through these young pines of various ages towards our next stop. When we reach it, if we look to the south, we’ll see an addition to the original LEAFS site. Much of it was covered in good-sized slash pine, invading over the years while fire was excluded. Those were harvested in 1996 and now longleafs are being restored to this part of the site. Our interpretive trail was laid out before all that happened and doesn’t go into the addition, but when you visit in person, you can detour along the firelines which break the addition into small sections.

While you’re there, you might look for some additional plants which favor wetter areas, such as pinebarren goldenrod (Solidago fistulosa), honeycomb head (Balduina uniflora), or rayless golden rod (Bigelowia nudata). When you’ve finished, come back here and continue along the main trail.

Meadow Beauty is another common flower which you’ll likely encounter. There are about a half-dozen different species in north Florida. A few more are found as far north as New England where Henry David Thoreau compared the distinctive urn-shaped fruit to a little cream pitcher.

Anywhere along the trail you may even find some flowers growing in it, despite the regular mowing. One of the more common is this bright orange Candy Tuft (Polygala lutea). Now let’s continue on to Stop 11. There the entry in the Trail Guide isn’t about flowers, but birds and other wildlife: 11. Stop here and listen. At any time, but particularly early on a spring morning, you’ll likely hear birds calling. The Eastern Towhee (formerly known as the Rufous-sided Towhee) is perhaps the most common bird of the pine flatwoods. Its call can sound like its name—a dry rattled tow-heeeee—or maybe even like Drink your tea-eee. Another common bird—more likely to be heard than seen—is the Common Yellowthroat. The male of this sparrow-sized bird has a distinctive black mask over his eyes and makes a variety of sounds, mostly a variation of a slurry witchity, witchity, witchity. Another bird with a typically three-parted call is the Carolina Wren: teakettle, teakettle, teakettle. You might think prescribed burning is harmful to birds and other wildlife, but quite the opposite is probably the case. After a fire, many birds take advantage of the abundant food supply of insects and spiders killed or crippled by the fire. Later, tender young shoots of new growth sprout up, providing a feast for a variety of insects which, in turn, are eaten by birds, as well as other animals. The new growth is also enjoyed by herbivores, such as deer, box turtles and gopher tortoises, and rabbits.

Actually, there are only a few spots on this site which are suitable for gopher tortoises, as most of the site is too wet much of the year for their burrows. When you visit in person, if it’s during a wet winter when there is little evaporation of rainfall, parts of the trail in this area could be a little wet—or even underwater. Now we’ll make a sharp turn and start heading back towards the parking area. If you’re tired of walking, there’s a bench just ahead where you can rest for a while. When you’re here in person, if you’re taking this walk in summer, perhaps the bench will be in the shade. But perhaps not. Although the bench is under some taller longleafs, their open canopy provides only shifting shade. There are only a large few trees here, but if you’ll imagine acres and acres of mature longleafs, all with open crowns like these, you’ll see why groundcover under them can be filled with such a variety of sun-loving species. Natural stands of longleafs don’t close in and make a shady forest, but rather a very open one. When you’re ready to move on, we’ll walk just a few feet to our next stop: 12. The LEAFS tract is now very gradually sloping downwards. You may continue to the right or return to the parking area by going left. To the right, the unmarked trail loops through several places where there may be standing water and the trail is often wet. In these areas, slash pine increasingly predominates, even among the larger trees. It is a species frequently found in wet areas, ones which are periodically saturated. Obviously, fires do not travel well into such areas, so longleaf pines are less common, although they do occur. In fact, the botanical name of longleaf pine—Pinus palustris—literally means “the pine that lives in marshy places.” The management objectives of the LEAFS project in the wet areas to your right differ somewhat from those in the areas you have just walked through. In order to ensure that the slash pines will not be damaged before reaching a marketable size in a few years, only very “cool” prescribed burns in the winter months will be undertaken. Once the slash pines have been harvested, there could be a “hot” site preparation burn. Then longleafs will be planted and when they are established, a more normal fire regime will be instituted.

We’re completing our loop now. You’ve walked through much of the site and in a moment will be looking back across one of the areas you’ve already seen from a different angle. At Stop 13 the Trail Guide refers to longleafs in the grass stage, but as you can see from this picture, many of those are well out of the grass stage and are making height growth. Here’s the guide entry: 13. As you walk beyond this marker towards the parking area, you will be passing through the area first planted in 1994 which you saw earlier from another spot. It has now been burned several times and more longleaf seedlings have been hand planted in bare spots. You’ll see many young longleafs well out of the grass stage. Can you also find a few longleaf grass stage seedlings amongst the real grass and other ground cover? It may be difficult to do so, except after the area has been burned; then they readily stand out. When these seedlings are well-established and have reached a larger size, this area will be burned again.

That was our last stop on the trail. Soon we’ll see the scorched vegetation of that burned area we passed at the start of our walk. In a few hundred feet, you’ll be back at the parking area.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this virtual walk and that you take a similar walk on our Lake Alto Park site. Even better, please visit the sites in person some time. Again, thanks for taking this walk with us.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)