| |

Lake Alto Park Site |

Our walk begins in the parking area in Lake Alto Park. When we drive up, we see the sign directing us to the interpretive trail.

Looking across the park, we see the LEAFS signs where the trail begins.

At the informational kiosk can read about longleafs and restoration and pick up a Trail Guide for the numbered stops along the trail. As we walk along, we’ll pause at each of the stops and read the entry in the guide. Perhaps you’ll have some questions. If so, we’d be glad for you to contact us.

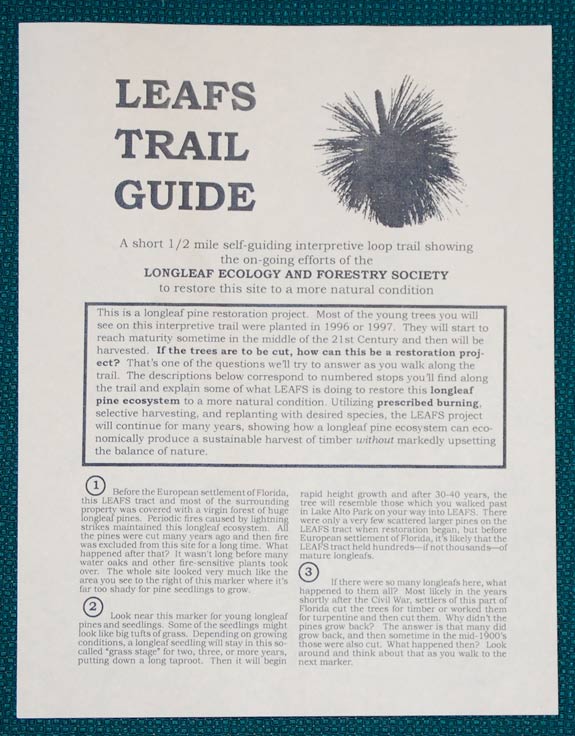

Before we begin walking, we read the introduction to the Trail Guide which tells us: This is a longleaf pine restoration project. Most of the young trees you will see on this interpretive trail were planted in 1996 or 1997. They will start to reach maturity sometime in the middle of this century and then will be harvested. If the trees are to be cut, how can this be a restoration project? That’s one of the questions we’ll try to answer as you walk along the trail. The descriptions below correspond to numbered stops you’ll find along the trail and explain some of what LEAFS is doing to restore this longleaf pine ecosystem to a more natural condition. Utilizing prescribed burning, selective harvesting, and replanting with desired species, the LEAFS project will continue for many years, showing how a longleaf pine ecosystem can economically produce a sustainable harvest of timber without markedly upsetting the balance of nature.

The trail begins by heading along the boundary between the park and the LEAFS site. We’ll walk through the shade of some oaks and within a few feet we come to our first stop.

At Stop 1, we note a young longleaf pine and read the entry in the Trail Guide: 1. Before the European settlement of Florida, this LEAFS tract and most of the surrounding property was covered with a virgin forest of huge longleaf pines. Periodic fires caused by lightning strikes maintained this longleaf ecosystem. All the pines were cut many years ago and then fire was excluded from this site for a long time. What happened after that? It wasn't long before many water oaks and other fire-sensitive plants took over. The whole site looked very much like the area you see to the right of this marker. It’s far too shady here for pine seedlings to grow.

As we walk down the trail, we note the contrast of the shady area mentioned in the guide to our right, with its tangle of small oaks and vines, to the sunny area on our left. There everything has been burned at least three times since the LEAFS restoration began. That small area to our right that we’ve just read about was not burned, and you can readily see the difference.

You’ll also see a contrast as we continue along and come up to Stop 2. These pictures were taken a few days apart in July 2010, one before a prescribed burn and the other afterwards. On this virtual walk, when we can be in the same place at two different times, you can see the difference. Here at Stop 2 we can read the entry about longleaf pine seedlings: 2. Look near this marker for young longleaf pines and seedlings. Some of the seedlings might look like big tufts of grass. Depending on growing conditions, a longleaf seedling will stay in this so-called “grass stage” for two, three, or more years, putting down a long taproot. Then it will begin rapid height growth and after 30-40 years, the tree will resemble those which you walked past in Lake Alto Park on your way into LEAFS. There were only a very few scattered larger pines on the LEAFS tract when restoration began, but before European settlement of Florida, it’s likely that the LEAFS tract held hundreds—if not thousands—of mature longleafs.

Here are two grass stage seedlings. The one on the right has put out a “candle” and is about to start height growth.

Where we’re walking now is very open, with very little shade. (When you visit in person, remember to bring a hat!) This site was cleared for pasture many years ago and most of the native ground cover was destroyed. The plants which have established themselves are, for the most part, also native to our area, but they now occur in a very different mix. No doubt saw palmetto and gallberry occurred here in much greater densities than we find now, and the grasses and bracken fern which we see all around us were once restricted to a few openings. Our next stop, just across a fireline, will tell us some more: 3. If there were so many longleafs here, what happened to them all? Settlers of this part of Florida, most likely in the years shortly after the Civil War, cut the longleaf pines for timber or worked them for turpentine and then cut them. Why didn’t the pines grow back? The answer is that many did grow back, and then sometime in the mid-1900’s those were also cut. What happened then? Look around and think about that as you walk to the next marker.

The next stop is not far away and is on a small mound. Standing on it gives us a chance to partially see over the vegetation.

Before the longleafs planted on this site started to come out of the grass stage and make height growth, from the mound you would have had an unobstructed view like this across a sea of bracken fern to the treeline marking the edge of Lake Alto. At Stop 4, in suggesting answers to the questions posed at Stop 3, the Trail Guide also discusses why there might be so much bracken fern: 4. Stand up here to look over a good part of this LEAFS tract. If you have visited the other LEAFS tract, about a mile south on CR 1471, you may have noticed how much the understory here differs. Generally on the other tract, there is a thick understory of palmetto and gallberry. Here there are grasses and other herbs, bracken fern, and smilax vines, with only a few scattered shrubs. Why? Perhaps sometime after all the trees were clearcut, the site might have been cleared for pasture and grazing of cattle. The presence of cattle probably contributed to the inability of many native plants to become reestablished here. Once the cattle were removed, water oaks quickly took over and now, with the oaks coming under control, these sun-loving species are proliferating.

One of the initial steps in preparing this site for restoration was the application of herbicide from a helicopter to the larger water oaks that had grown up during the years of fire exclusion. Neither the herbicide nor the periodic fires have completely eliminated water oaks from the site and they continue to be a problem. They can grow quickly and shade out young longleaf seedlings. After the sections where we’re walking were burned in 2001 and in subsequent years, individual sprouts have been treated with herbicide from a backpack sprayer. But there still are many water oaks here.

Water oaks can be quite persistent. A hot fire will kill the aboveground trunk of young trees, but the roots survive and quickly send up new shoots. Larger trees have thicker bark which can sometimes protect them from fire. When these are cut, they also quickly resprout. At the stop we’re coming up to, a few water oaks were left for you to see how much shade even young trees can make.

As we come up to Stop 5, the trail appears to go straight ahead between these two young water oaks. But the Trail Guide gives us a choice as to which way to go: 5. Near this marker are young water oaks. Before this restoration project began, this site was crowded with many trees of this species. They made so much shade that very little else would grow here. To prepare for restoration, it was necessary to apply a herbicide to the whole site from a helicopter. Once the oaks died, the site was burned and then planted with 25,000 longleaf seedlings. From here you may walk straight ahead for about a quarter-mile through 20 acres of these planted pines to reach the Lake Alto-Little Lake Santa Fe Canal, dug in 1877-1879, and at the time the only way to reach Melrose from Waldo. Or you might turn right and walk down to Lake Alto through the shady swamp which surrounds the lake; if you do, notice how the vegetation is markedly different from that up here on the higher ground. Either way, when you’re ready, return to this marker and continue on up the trail to your left on the old roadbed to the next marker.

This old woods road was put in many years ago by former owners. Let’s walk down it towards the lake where we can get in the shade for a bit.

The lake level fluctuates and in the heat of the drought in the summer of 2001 it was quite low. Now that our rains have returned to a more normal pattern, sometimes the water from the lake will reach up here into these cypress trees. Although you might be able to find a few blackened tree trunks, generally where we are now doesn’t burn well.

There are a lot of cinnamon ferns and netted chain ferns on either side of us, two common wetland species. Now we’ll walk back, past that last marker, and go up the old road until we come to another shady spot.

Here we are. We’ve passed an intersection of firelines and we’re almost to Stop 6. There the Trail Guide tells us: 6. As mentioned earlier, natural fires caused by lightning strikes maintained the virgin longleaf ecosystem which once occupied this site. In the millions of years in which longleaf pines evolved in the presence of natural fire, they became very fire-adapted. The thick bark of mature trees can withstand all but the hottest fires. Longleaf pine seedlings easily survive fires which sweep quickly over them, burning their needles, but leaving the growing tip unharmed. Now that pines have been planted here, prescribed fires which mimic natural fires burn this site every couple of years and help control competing vegetation. The areas to your left have been burned several times since this restoration project began; note the difference to your right. Ahead, please turn to your left.

As we walk up to the turn mentioned in the Trail Guide, to our right is an area burned in July 2010. It is a section of the LEAFS site which has only recently been acquired. The tall trees mark the former property boundary and as the Trail Guide indicates, this section has not been burned as often as the section on the other side of the trail.

The former owner of this section planted much of it with slash pines in the 1980s. As we look across the recently burned section, we can see the rows of planted pines in the distance. In a few more years, these will have reached the size where they can be cut for pulpwood. Then restoration to longleaf can commence.

Let’s walk up to that turn mentioned in the Trail Guide, make a left, and start looping back to the trailhead at the park.

As we make our way back towards the park, we come to Stop 7 and an example of some of the larger pines on the site. Not all of these pines are longleafs, as the Trail Guide tell us: 7. As you stand here, you can see some of the larger pines which were on this site when restoration began. Because they were so scattered, it’s not likely they would have produced enough seed to regenerate this site with many pines. Additionally, the many years of fire exclusion had allowed loblolly and slash pines to become established; they are very much less fire-tolerant than longleafs and most of their seedlings will be killed by prescribed fires. So it was necessary to plant the site. Years from now, these young planted trees will reach maturity and start producing seeds. At that time, they will be able to regenerate the site, thereby saving the expense of replanting. Please turn left again here.

The elevation where we’re walking now is about ten feet higher than down by the lake. Its sandier and drier and the longleafs planted here are doing well.

In another 15 or 20 years, when the young trees in this picture are as thick as the older tree in the center, they could be thinned and some 20 years after that, quite profitably harvested for saw timber. The Trail Guide at stop 8 discusses what would happen then: 8. When these young trees are large enough to be harvested, only some of them will be cut at any one time. Enough will be left standing to regenerate this site as a longleaf pine ecosystem far into the future. Small private landowners—those with only a few acres or up to several hundred acres—might manage their property in a similar manner through the use of prescribed fire and selective harvesting. While such small landowners may not own enough property to engage in timber production as a full-time occupation, they can still enjoy some income while at the same time maintaining their property in something resembling a natural condition. But the use of prescribed fire causes some special problems, as we’ll discuss at the next marker.

So far on this virtual walk, we haven’t seen any wildlife. On a real walk, unless you’re very lucky, you probably won’t see any of the dramatic animals which inhabit this site such as rattlesnakes, foxes, or deer. However, you probably will see some birds. Towhees and woodpeckers are fairly common. There are woodpecker holes in snags.

Under a large pine tree you might find a chewed up pine cone, evidence that a squirrel has made a meal of the seeds.

Now we’re nearing the end of our walk. From here, you can see the park and we’re almost at our last stop on this loop trail. As we come up to it, we pass a clump of what are probably sand live oaks, trees very similar to and sometimes hard to tell apart from the larger stately live oaks. Sand live oaks are found more often in drier sandy soils such as these. Most of this site can be classified as pine flatwoods, but there are spots which more closely resemble sandhills. This is not uncommon, as the two ecosystems often grade into each other, separated by only a few feet (or inches!) in elevation.

We’re coming up on Stop 9. If you’re lucky, you might see a gopher tortoise near here; there are at least a half dozen burrows close to the marker we’re approaching. Their presence is another indicator that this part of the site is sandier and drier.

The trail we’ve been walking on is also used as a fireline. Firelines break this site into over a dozen burning blocks. Prescribed fire is an important management tool here at LEAFS and at other places where longleafs are grown. The final entry in the Trail Guide emphasizes how vital it is: 9. Lake Alto Estates, just across the road leading into Lake Alto Park, is home to over 50 families. The presence of so many people nearby creates a smoke sensitive area. Such smoke sensitive areas are more and more common as Florida becomes increasingly populated and make it difficult to undertake prescribed burning, as property managers must make every effort to direct smoke away from such areas. For the LEAFS restoration project—where prescribed burning is such an important part—it is fortunate that the tract is not surrounded on all sides by roads and homes, because as things are, smoke need be directed away from only one direction. If the tract were surrounded, it might not be possible to burn at all. Dangerous levels of fuel accumulate in such situations, and as recent dry years in Florida have shown, wildfires often result, sometimes with disastrous effect on nearby homes. Prescribed fires, in addition to preserving the longleaf ecosystem, also reduce the likelihood and severity of wildfires.

That was our last stop on the trail. With one more turn to the left, you’ll be back at the trailhead opposite the parking area. We hope you’ve enjoyed this virtual walk and that you take a similar walk on our CR 1471 site. Even better, please visit the sites in person some time. Again, thanks for taking this walk with us.

|